Harper Lee’s long-awaited second novel hit the shelves this July – and it was a literary event like no other. It had been more than fifty years since the publication of the seminal To Kill A Mockingbird, and the hype surrounding Go Set A Watchman certainly felt the burden of this time lapse. Was it worth the wait? Annette Ong reviews the book of the summer for Soapbox.

“You never saw him as a man with a man’s heart, and a man’s failings – I’ll grant you it may have been hard to see, he makes so few mistakes, but he makes ‘em like all of us” – Uncle Jack.

Published decades after To Kill a Mockingbird, reclusive author Lee has released her second novel Go Set A Watchman to much fanfare. The questions circulating the literary community, amongst fans and publishers alike, are: Is it any good? How does it rate in comparison to Mockingbird? Was it worth publishing at this late stage?

To tell the truth, I’m not entirely sure. I’m still in two minds. It’s a good read and there is all the evidence of Lee’s trademark wit and intelligence, but does it add anything to the legacy of Mockingbird? Did we “need” this book? I’ll let you decide.

(For those of you who are yet to read it: this review contains spoilers).

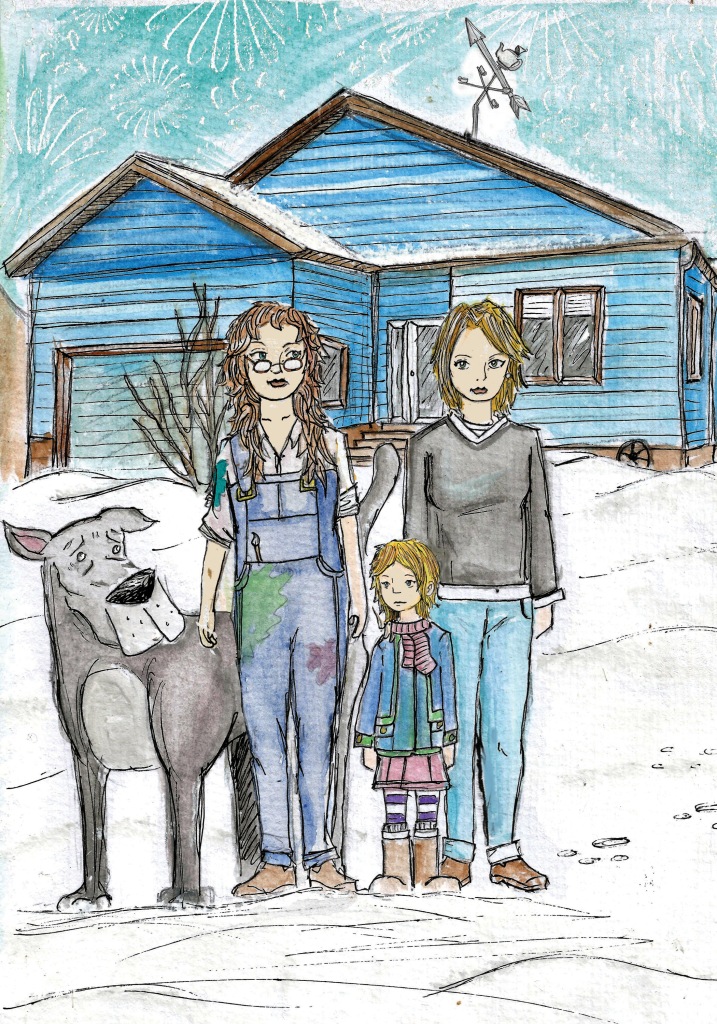

Go Set a Watchman is the sequel to Lee’s magnum opus To Kill a Mockingbird. Set 20 years later, it follows a 26-year-old Jean Louise “Scout” Finch, on a holiday back to Maycomb County. Scout has been living independently in New York and is courting her father’s protégé, Henry Clinton. Atticus Finch has arthritis and is being cared for by his sister, Alexandra. Jem, Scout’s beloved brother, has passed away and her childhood friend, Dill, has moved, having never returned after the war. An aged Calpurnia is being cared for by her family.

Scout discovers there have been significant changes in town since she’s been away. Sadly, she finds both her father and Henry are on the Maycomb County Citizens’ Council; in fact, Atticus is on the board of directors and Henry is a fervent member. Her suspicions as to what goes on at these council meetings is first aroused when she finds a racist pamphlet in the family home.

The biggest revelation and perhaps the most unsettling, is that Atticus Finch is a bigot (please say it isn’t so!) Or is he just a product of his time? Or is he infiltrating the enemy camp so he can take them down from the inside? This new information throws Scout into a deep moral turmoil – one which her Uncle Jack helps her to navigate.

Scout is devastated by the fact that she suddenly doesn’t really know her father. Atticus Finch, a highly respected paragon of virtue and decency to her, is perhaps not as progressive and accepting as she once believed. Scout is not “colour blind” as the novel suggests; she sees colour but it doesn’t matter to her and she cannot fathom anyone thinking otherwise.

The novel deviates from the present day to Scout’s memories, but, although entertaining, doesn’t reveal anything new. There are many flashbacks to happier times that don’t really add anything substantial to the plot. However, it is pleasant to revisit old characters again.

Go Set a Watchman will always be preceded by the reputation of Mockingbird. There is no comparison between the two and it is certainly not a blight on Mockingbird at all, though I feel it will leave fans divided as to its relevancy for a long time.